Hello there. Happy to report that I’m still alive – in spite of Thanksgiving’s best efforts! And I’m back to making sure that my players won’t be. Until Christmas inevitably gets me on the back-swing.

I’ve been pretty busy with things other than Doorways 9 during November – hence the lack of posting. But in the last few days I was finally able to buckle down, and get to work on my goals for the month. The results have been pretty good, in my opinion. I suppose you’ll be the judge of that for yourself.

Anyways, here’s the story of how I came dangerously close to building my own Ren’Py in Godot.

Part 1: I just wanted the eyeball to talk to me.

Doorways 9 is not a visual novel. Not really. If I had to put a simple label to it, I guess I’d have to go with… puzzle-platformer? Maybe a bit of bullet-hell, if I’m being generous? I don’t know. None of those really describe its gameplay, but I’ve yet to find a game storefront with a “Computer Setup UI” category.

Regardless, my point: from the very start of development, I’ve never thought of it as a visual novel.

…

And yet… looking through the hours of test footage and devlogs on my hard drive, you wouldn’t necessarily know that. If it walks like a visual novel, and talks like a visual novel… What gives?

Well, the game designer’s answer is that, for a variety of reasons, I really, really wanted my knock-off Cortana to talk to the player. That’s partly for the atmosphere – a fusion of the classic:

“I’m trapped in a small box with a vengeful machine!”

–Terminator, 2001, etc.

-and my own, real-life I.T. experience of:

“I have received more than 30 popups asking me to install McAfee antivirus today, and if I get one more I will absolutely lose my mind in the middle of this basement”.

-Me, circa July 2023

The point being to have someone or something there, berating and obstructing you as you try to do simple tasks – to make the obstacles feel a bit less like obstacles.

…That said, the more honest answer would probably be that I watched someone play Portal 2 as a teenager, and the idea of a robotic eyeball doing color commentary on your gameplay cemented itself in my brain forever.

Of course, the main problem with wanting a character to talk to the player is that you need some sort of system for actually doing that. But it can’t be that hard, right?

…Right?

In all seriousness, setting up a dialogue system actually wasn’t that hard. Making a character talk isn’t exactly an unsolved problem, and even then I wasn’t really pushing the envelope with what I was doing. Far from it, actually – I was deliberately avoiding anything “too complicated”. I would be setting up a text box that I could show/hide around Ayanna, nothing more.

Back in September, I wrote a little bit about how I envisioned my work on dialogue, going forward:

“…I’ve rigged up the chat HUD with a few preset modes that I can switch between at any point. By combining them with her existing movement patterns and animations, and hooking them into my scene transitions, I’m aiming to be able to create some more complex, dynamic conversation sequences – with (relatively) little extra overhead on my part.”

– The Eyeball Speaks to Me (September 28th, 2023)

Keep in mind that this was still my first week or two of working in godot, and I was still trying to get a handle on what the engine could do. At this point, everything I was doing was more of a proof of concept for myself – proof that I could create what I had in mind, rather than a well-structured architecture.

In less than a day’s work I had a little dialogue box set up in a singleton, which I could easily call from any script to display messages to the player. All I had to do was write a few scripts for each level, and have those determine when things should be displayed. Easy!

…

Oh no. It isn’t actually that easy, is it?

Part 2: No. No, it isn’t.

Setting up a text box is easy. Setting up a dialogue system? Less so.

At the time of my original test, I was already working on a system that managed the intros and outros of each level. So, when I needed to test displaying text, I just hard-coded Ayanna’s introduction into it, as an override to the normal intro script.

That worked – but it was:

- Sort of a hassle to get working in the first place

- Definitely going to be annoying to repeat for each level

- Not going to work for any chatter outside of the intro/outro

Obviously, I couldn’t continue like that. I’d lose my mind. So, my first instinct was to try and make the the way I handled dialogue a bit more generic; to make the messages and displays their own script, so that I didn’t have to manually write new conversation code for every single level.

In my testing, I kept it simple – with a script that would iterate through messages. That’s fine for something like an introduction, but quickly runs into problems the second you want to do anything remotely interesting.

For example, in my outline of a later level, I had an interaction that went:

- The player toggles off data access.

- Ayanna interrupts, asking to talk 1-on-1.

- The first text box is timed, and un-interruptable.

- Subsequent text boxes require the player to press a button.

- The window fades away.

- Ayanna moves to the center of the screen.

- Ayanna informs the player that collecting their data is, in fact, her whole job.

- …and she’d appreciate if they would just make this easier.

- Ayanna move back to the corner of the screen.

- The window fades back in.

- Ayanna glances over at the checkbox for data access.

- She realizes that it’s still unchecked.

- She re-checks it.

- She hands control back to the player.

Looking over all of this, I realized pretty quickly that trying to make a separate “dialogue” system is a bit of a fool’s errand, beyond the UI side of things. It assumes that your dialogue is separate from the rest of the game – the screen, the animations, everything – which it isn’t. You aren’t grafting a book onto the side of a video game, you’re making a game where the characters talk.

The real question, then, is this:

With all the tools at your disposal, how do you make conversation mesh with your gameplay?

Part 3: Ren’Py is Now Involved.

Doorways 9 is not a visual novel. Not intentionally.

…

I am, however, also making one of those.

I’ve been messing around with Ren’Py for about a year now, for a visual novel I’m working on with some friends. Between Riverboat Pachinko, Doorways 9, and life in general, it’s been on the backburner for most of 2023 – an occasional break from all the C# every few weeks.

(Sorry to my fellow devs. It’s on the top of my list after this project!)

Ren’Py, as a game engine, is something I would rate an “It’s Neat.” out of 10. It’s (clearly) good for visual novels and narrative games, and makes setting up dialogue a breeze – in comparison to whatever I’m doing over here. I find that it gets cumbersome when you start moving into, say, more convoluted gameplay stuff, but that’s neither here nor there, as far as this blog goes.

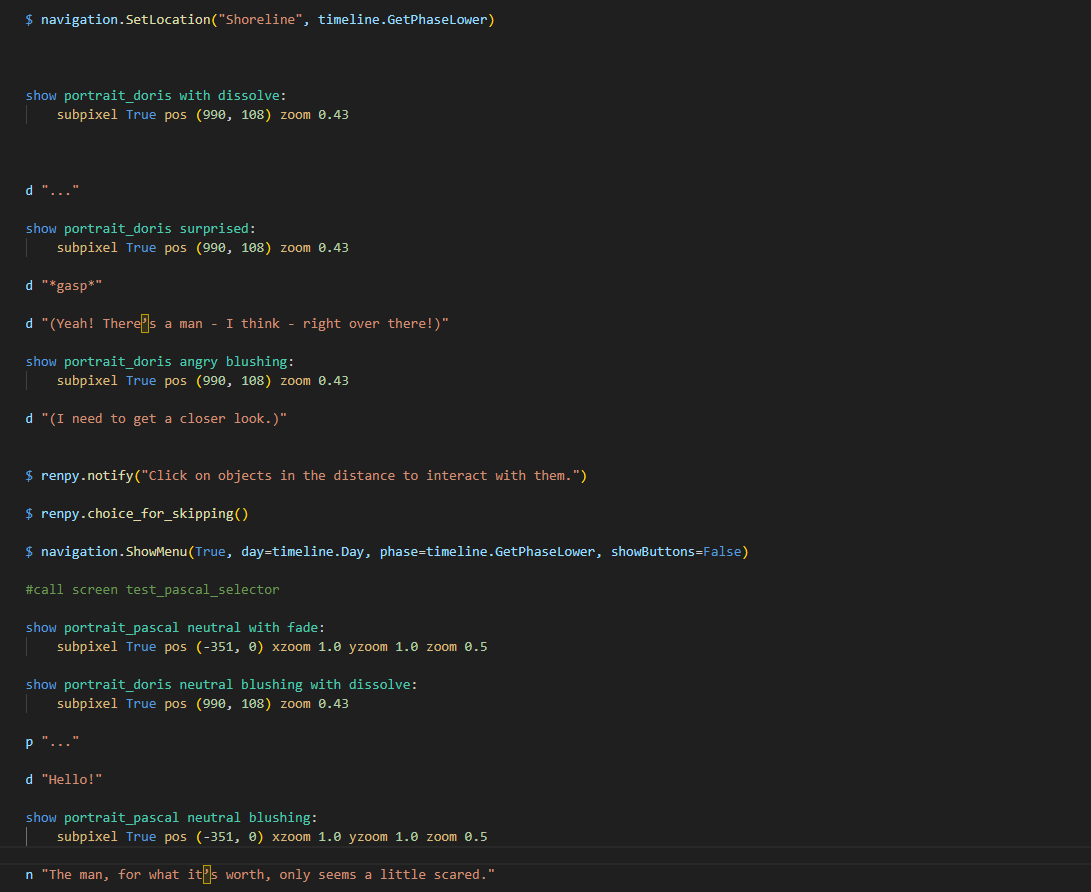

One of the things I’ve liked most about Ren’Py so far is its relationship between scenes, events, and scripting. Most of the time, you can write out your in-game events as if they’re a script (the movie kind) and insert calls to other events or python code as-needed.

That’s pretty useful! It’s also basically the functionality I wanted for Doorways 9 – and a framework for how to organize it. It was just a question of how best to replicate that with the tools available in Godot…

Part 4: A System for Actually Doing That

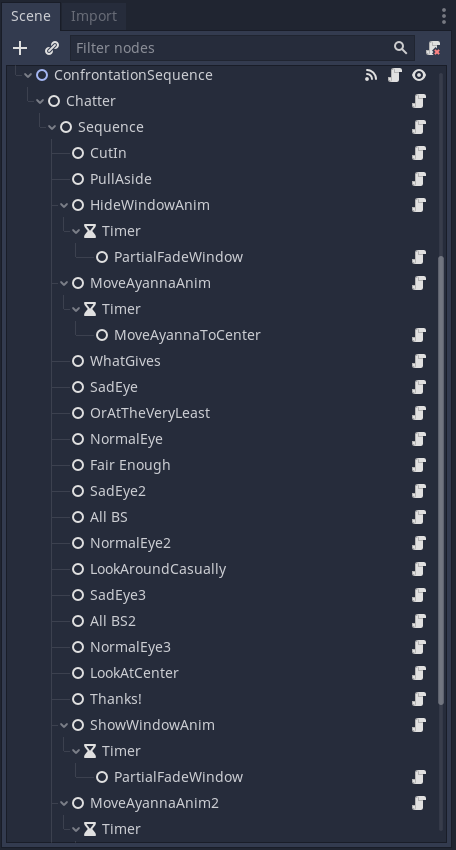

Initially, I considered sticking close to how Ren’Py does it; making a script for each sequence of events I wanted, and then calling them from the level. However, for the sake of expediency in level-building, I ultimately decided to keep things modular, using Godot’s Node hierarchy.

The idea here is pretty simple: Take all of the events and actions I’m going to need and map each one to a node.

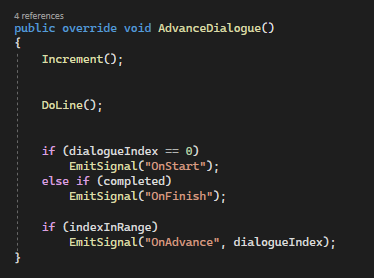

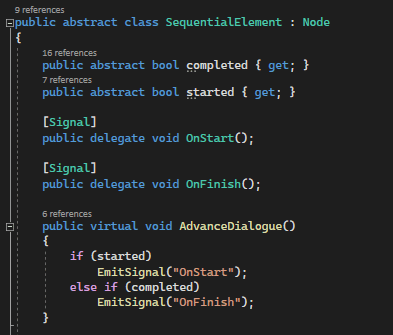

Each node inherits from a base class for sequence elements – which provides the basic framework for checking if they are completed or not.

Each node is responsible for a single behavior.

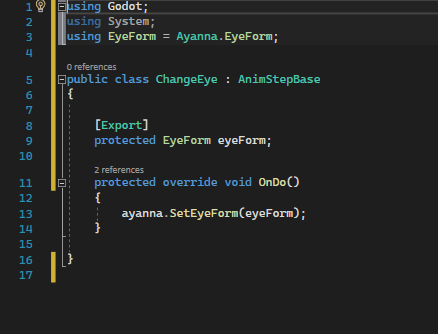

For some, this takes the form of a simple, instant trigger – like changing an animation, or updating a display.

This block, for example, inherits from a base class for Ayanna’s animations – and changes the active sprite for her pupil.

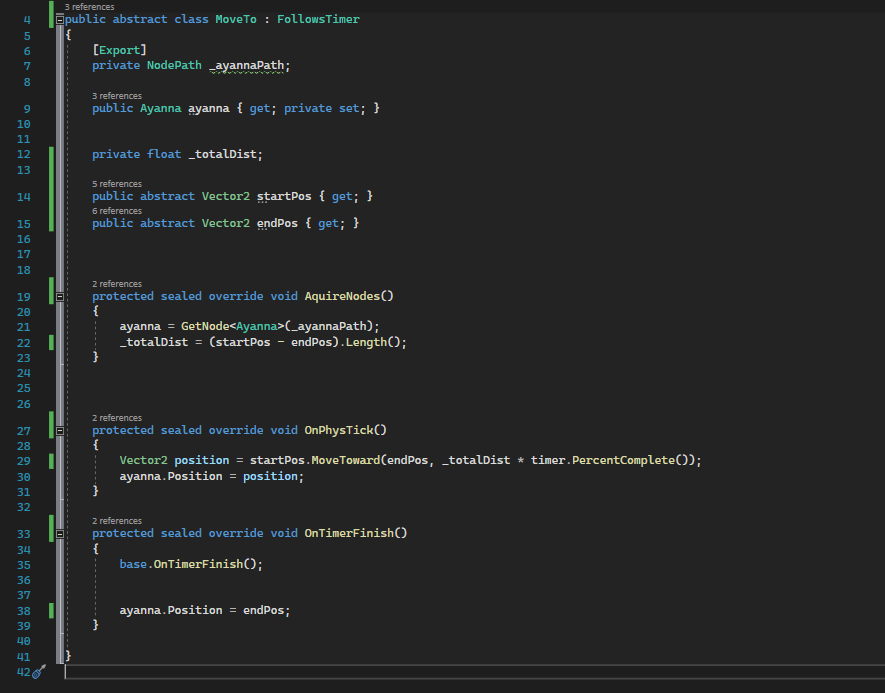

Others have more complex behaviors – and conditions to satisfy before being flagged as complete.

Some, like this script for moving Ayanna, won’t mark themselves as complete until a timer has run its course – and will move her from point to point over the timer’s duration.

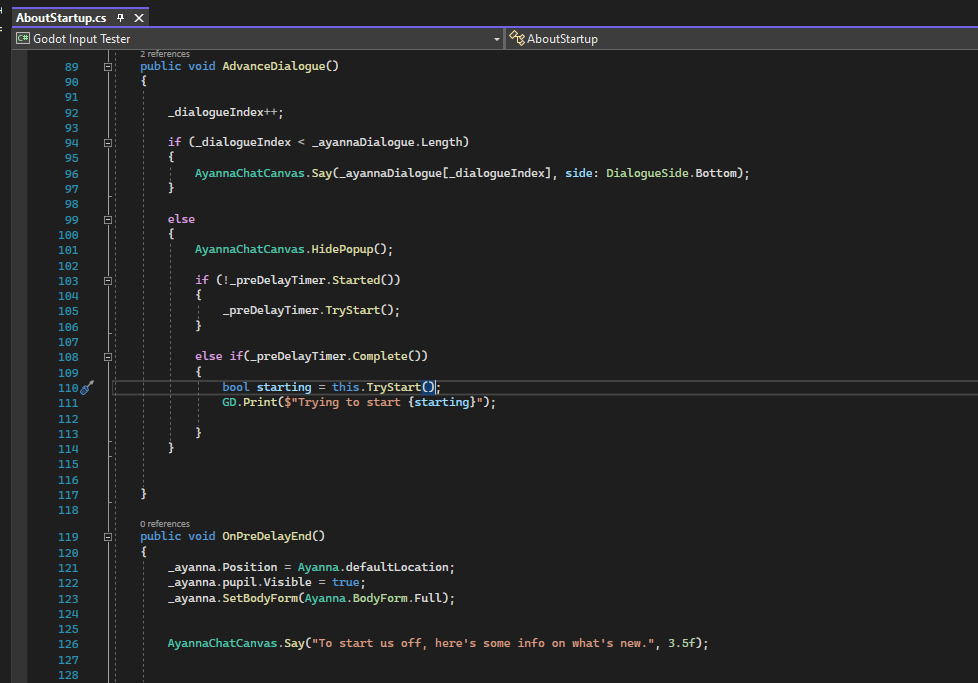

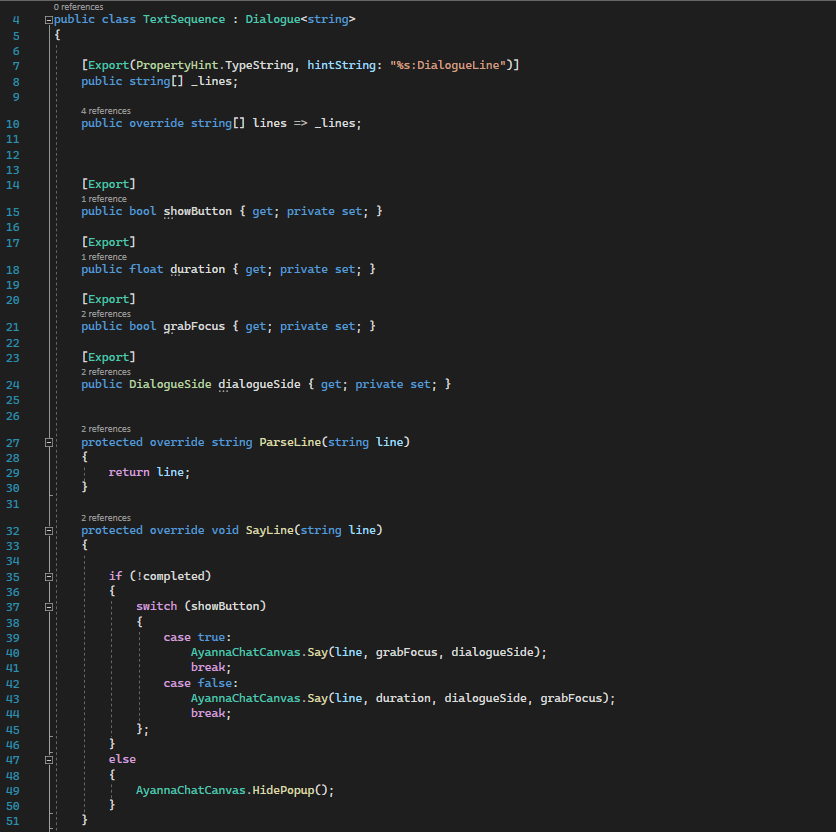

There are also several which take over handling dialogue – adapted from my original test scripts.

This one – which I’m currently using for most of my dialogue – simply iterates through a set of strings, marking itself as complete once all have been displayed.

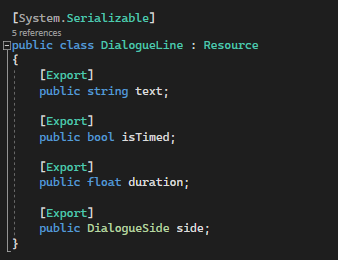

The message display settings have also been moved to these nodes – replacing the DialogueLine resource I showed earlier.

Frankly, I don’t know why I didn’t do it this way in the first place. It’s far, far less irritating to work with.

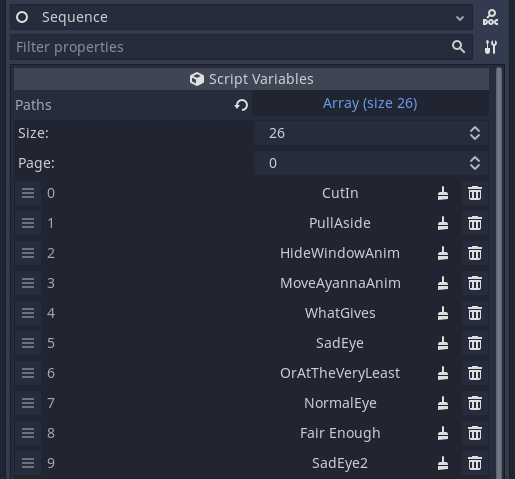

All of these are fed into a Sequence node – which, when called, will attempt to iterate through elements until all are complete.

This is, functionally, my stand-in for the label system in Ren’Py – a start point in a chain of events which is publicly accessible to the rest the scene.

I like this because it helps de-clutter the code – the gameplay scripts can continue to be gameplay scripts, and event triggers can handle any special animations or dialogue I need for a level.

All of these nodes can be freely assembled in the editor hierarchy, to create chains of complex events from simple components.

As intended, this system is very modular, and pretty easy to organize. In theory, with the way Godot’s nodes work, I could even cordon these sequences off into their own scenes, if I wanted to reuse them somewhere. Or was just sick of big hierarchies.

This example shown here is taken from a “Language Select” stage that I’ve been working on – and actually plays out the sequence of events I used as an example earlier. Each node is essentially a single point from the outline – with several extras added in – which is a level of parity between documentation and implementation that really satisfies some part of my designer brain.

And, just like that – I’ve got an event system! One that’s flexible to let me do everything I wanted, and straightforward enough that I can do most of my work with it right in Godot’s editor! The only thing that remained at this point was…

Well… to put words in her non-existent mouth.

Part 5: She Has No Mouth But She Still Screams

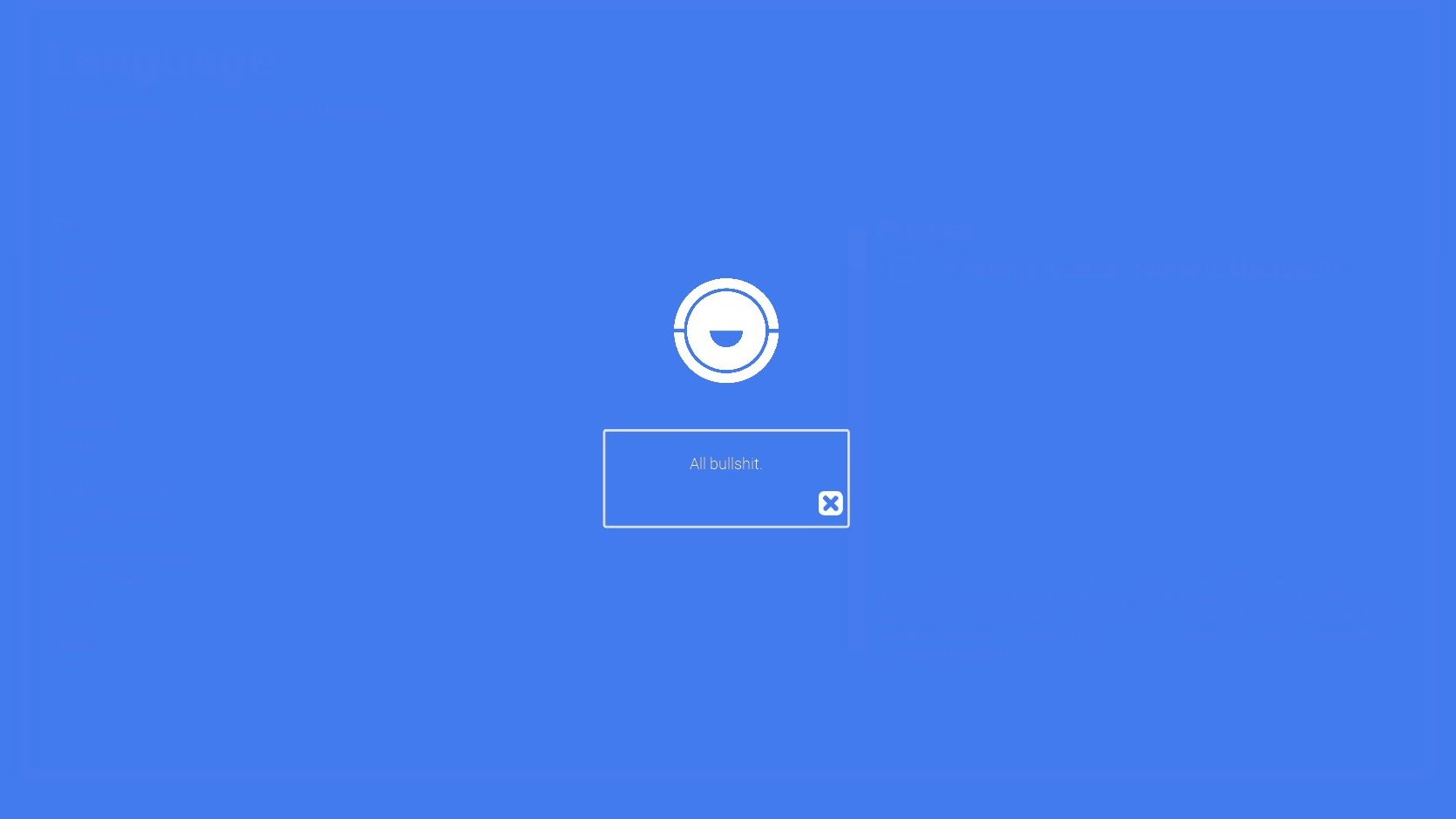

So, all put together, what does this system look like in action? Well, it looks something like this!

Once I’d gotten the system setup, the turnaround time on making this interaction was almost comical, in comparison to the introduction I’d created earlier in the project. I ended up writing a few extra scripts, as I encountered functionality that I needed – but the experience was generally a plug-and-play deal. However, there were one or two extra things I ended up doing, to add a bit of flair.

For one, by the time that I had this dialogue segment done, the silent pop-in and pop-out of text had started to feel a bit hollow – so I decided that it was finally time to give Ayanna her own “voice”.

Step one was the text scroll – which was just a little bit of code tacked onto the chat canvas that printed messages at a rate over time. Nothing fancy there, though I did once again find myself referencing Ren’Py’s text scrolling for ideas.

Step two was the sound of her voice – not spoken words (for now?) – but something to add texture to the dialogue. I barely qualify as a sound designer, so I started the same place I always do with these things: mashing a few notes into chrome music lab.

It’s nothing particularly interesting – just a few, vaguely musical clips to give her a bit of a singsong tone. I chopped those up into a few sound files, and did some editing to bring them more in line with the other system sounds for my fictional OS.

And so… that was it!

The system’s in place!

My girl talks!

…And all it cost me was one weekend!

Part 6: Well class? What did we learn today?

Well, I’m not sure it’s something I’ve newly “learned”, but the last few weeks have reinforced for me the idea that, as a game developer, it is your sworn duty to fling yourself headlong into the documentation for every tool you possibly can.

Not really. And, if your employer starts asking you to swear a paladin oath in the name of game design you should probably get outta dodge ASAP.

That said, it’s a pretty good idea to expose yourself to as many tools and concepts as you can – because your challenges absolutely will not limit themselves to a single genre.

Is Doorways 9 actually kind of a visual novel? I don’t know! Maybe! I don’t care!

I needed to figure out a way of making this whiny googly eye have a conversation with the player mid-murder – which was a very specific problem that I have definitely not encountered as a designer before. And if I’d sat around trying to trying to figure it out from scratch… I’d still be figuring it out now! But my experience messing with Ren’Py gave me a better foundation – an idea of where to start.

Chances are someone, somewhere has already come up with a solution to your problem – potentially while working towards something completely different. So… might as well learn!

Fin. And Housekeeping.

Oh no. I started writing this thing on Wednesday. It was November when I started this.

Oh well. That just means I’m getting back into it, knowing me.

I intend to have Doorways 9 added to my portfolio page on this site soon. So that’ll be nice.

As ever, I’m open for a job in game design, so if any of this somehow sold you on me, hit me up.

I’m also going back to visit Montreal after Christmas. If there’s a gap in writing for that week, that’s why.

…

Yeah. I think that’s it.

Thanks for reading this far, if you did. And have a good one!

Leave a reply to Knock, Knock. – The Chep Site Cancel reply