I’m coming up on about two years of playtesting and design consulting for The Dragon’s Table – a dark fantasy TTRPG system being designed by my friend, Samantha Arehart.

I haven’t written about it much – largely because it’s a tabletop system, and most of the online circles I run in are more geared towards video games than pen-and-paper stuff. It’s also because my work tends to take the form of short comments, appended to the game’s rule documents at 2 a.m. on the morning after a playtest session. Not exactly the basis for great reading material.

Recently, though, I had a discussion about map design that I think applies to broader RPG level design, and is actually worth writing about. Or, at the very least, deserves something a bit better than Google Drive’s comment system. So here it is.

Part 1 – Theater of the Mind

So, I started with TTRPGs in college, and – for the majority of my time playing – most of what we were doing bordered on theater-of-the-mind. We tended to have, say, a dry-erase grid to scribble vague shapes onto – but that was more of a visual aid than a map. It was the suggestion of an environment, rather than a space of fixed rules and features.

The lack of concrete, defined spaces can, on paper, be problematic for some players. I know that I’ve definitely been through a few encounters where my ADHD-riddled brain struggled to keep focus on the details of each round, and I’m certainly not alone in that. But, in general, I think that theater-of-the-mind has one big, slightly paradoxical advantage to it, as far as level design goes: it necessitates description.

Without description, an encounter in a theater-of-the-mind scenario functionally does not exist. If there is a feature of the map that players can make use of, need to avoid, etc. – and no clear visual reference for it, then you can’t just say-

“You’re in a room.”

-or they won’t have any details to work off of. Of course, there can be things hidden around a map, which players have to work to find. But even then, they need some sort of reference point – for the environment they’re trying to search, or for the fact that there’s something to look for at all. Cabinets, lakes, trees – anything that can ignite a spark in a player’s brain make them go-

“Hey. I’d stash something secret in there.”

-thereby kickstarting the search.

This, naturally, applies to both roleplaying and the combat/strategy side of RPGs. In order to roleplay effectively – to come up with creative ways of doing things and interacting with the world – you need a concept of what there is to interact with. Not much, necessarily, but something.

Likewise, in combat situations – and particularly in more formal combat systems like D&D or Pathfinder – you need to have some idea of what you have to work with in order to form a strategy. There’s the basics for tactics – defensible positions, enemy locations, etc. – but also, anything specific to the map itself. If there’s some sort of fundamental trick to the level, players need to know that there’s something possible, if not exactly what that trick is.

Part 2 – Maps Don’t Stand Alone

I don’t imagine that any of what I’ve written above is particularly new or insightful information – and the idea that you need to define an environment if you want players to interact with it is… a bit of a “water is wet” sort of observation, honestly. However, the game design hangup that I’ve been thinking about recently – and the reason for writing this in the first place – is this: Having a physical map, or even a description of your environment, is not an effective substitute for highlighting the mechanics and gameplay features of a ttrpg map.

Well, not necessarily, at least. Allow me to elaborate.

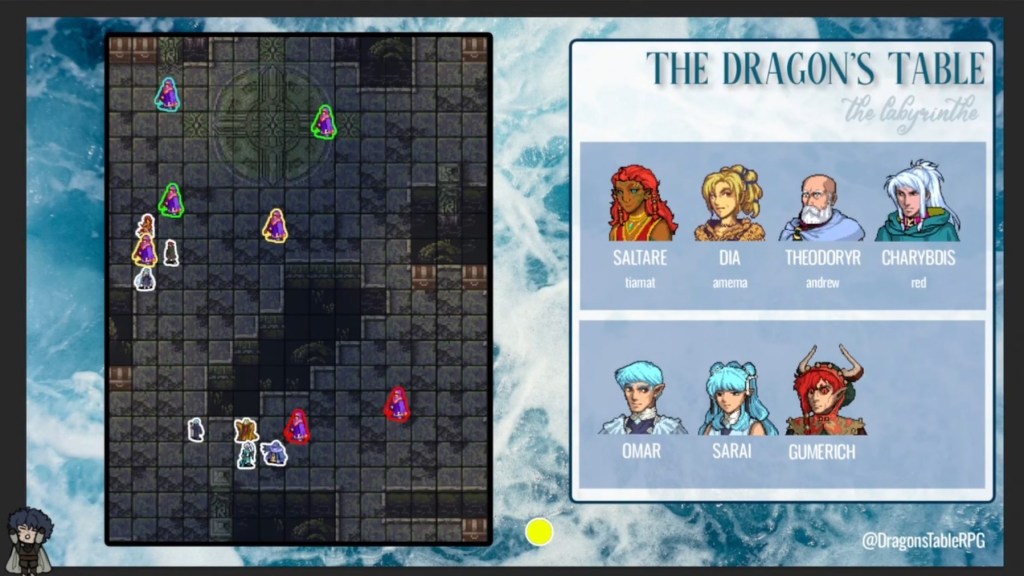

The thing that kickstarted this train of thought for me recently was an encounter we had in a test session earlier in the week. We’re doing a high-level character test of The Dragon’s Table right now, and we had a combat encounter on this map:

Obviously a good number of people reading this aren’t familiar with the system, and your vague idea of how it works will vary depending on how big of a Fire Emblem fan you are. But, suffice to say, there’s a fair bit of communication being done here at a glance. There’s chests scattered around the room, marking pretty clear side objectives, paths of varying width and… squigglyness to consider when moving units around. Pretty clear.

Now, as we got into combat, things started to drag a bit; the enemies were hard to hit, and did surprisingly pathetic amounts of damage for such high levels, and in spite of different tactics on our part, it was taking a while to make any progress.

As it turns out, there’s a reason for that. While we did make several perception/investigation checks during gameplay, it appears we missed a level mechanic that greatly speeds up the encounter.

What is that mechanic? I don’t know! I’m still playing, and that’d be spoilers 🙂

Despite that, I was talking about map design and – how to communicate level features – with Sam later that night. Rather than retyping my own words, I’m just going to pretentiously quote myself here:

“It’s the tiles, perhaps? A lot of background-lookin’ stuff“

“Like, in D&D – theatre of the mind stuff – you have to describe the environment features, verbally. With a map it kinda does some of the work – but can also flatten out player perception of the environment. Reduce it to squares and walls, especially if the ability to see and figure out stuff is roll-dependent.“

“Like, oops! My roll to investigate this area gave me only some basic info on the environment and enemies. So now I’m mostly working off that in planning my strategy.“

“The risk/reward of spending a turn to check (and/or fail) vs to grind out the combat part of the map from the safest position can easily come down on the latter side. Secret mechanics are one thing, but the main map feature (or the need to find it) has to be really upfront.“

-Me, October 2nd, 2023 11:11pm

It’s that last bit – the part about risk/reward and the action economy of a turn – that’s really wedged itself in my brain – and is responsible for me writing this. In a weird way, giving your players information on the layout of a map can softly discourage further investigation or engagement with the environment.

When you can see a tile grid laid out in front of you as a player, you don’t need to be constantly asking questions about your environment in the same way you would without that information. And, in a combat situation where a roll to investigate eats up part of your turn, and your character runs a risk of dying permanently, do you even bother? In a scenario like ours, where we had the basic knowledge we needed to keep our characters safe, blowing turns rolling (and potentially failing) to find another solution isn’t the most sound tactic.

As a brief aside, I want to be clear that this in no way reflects on my friend’s overall skills as a designer. There have been plenty of good maps through my time as a tester, and the one immediately before this was a very well done puzzle encounter. Scenarios where the players totally whiff do just creep up on you sometimes in game design.

But, I do see instances of this sort of thing a fair bit – across both TTRPGs and video games. Specifically when it comes to turn-based strategy and grid management, level mechanics meant to shake things up and make a map interesting sometimes just encourage players to retreat, and to take the safest, grindiest path to victory. Which is fine! But also, as a game designer, is one of those things that can just feel bad.

It’s something to keep in mind while working on level design stuff: keep the mechanics critical to your level clear – or else make it clear that there’s something the player need to figure out.

Oh dear god, that’s a long post. I’d hoped that basing this on some 11pm tweets would help bang out a quick little blog, but apparently I have thoughts. Unfortunate for me, but I hope you got something out of it.

I stealthily linked these things above, but for clarity, you can find more on The Dragon’s Table TTRPG here, or on the game’s twitter, where there’s regular design updates and character art.

Also, a special thank you to Samantha Arehart. A true friend is someone who gives you her blessing to write an essay inspired by her own design mistakes, and she did, in fact, do that. Aside from The Dragon’s Table, she’s also a terrific artist, and you should follow her.

Thanks to everyone who stuck around to read this, and I hope you all have a great rest of your day!

Leave a reply to Rollover: An Unnecessary Micro-Thesis on Dice-Rolling – The Chep Site Cancel reply