Hello! Welcome to the blog! Today, I come before you with a confession: real-time strategy games have been living, rent-free, in my brain for the last 10 years.

Now, there are plenty of good reasons to be thinking about real-time-strategy; it’s a famously obsession-worthy genre! That’s not really what I’m here to talk about, though. Not this time.

Instead, I’m here today with a short love letter. A love letter to a very specific a subset of the genre. Or, more accurately: to a type of mechanic.

You see, Tooth & Tail’s control scheme has been bouncing around in the recesses of my mind for a truly, disproportionately large part of my life – and I need everybody to understand why.

Part 1: A Lightly-Abridged Primer

Before I get into the specifics, I feel I have to make sure that everyone is on the same page about real-time strategy games – so that’s what this section is going to be. Apologies in advance if you already know most of this.

(Source)

Unlike the last time I had to do this, succinctly defining real-time strategy is one of those tasks that can be… tricky. This is one of gaming’s older genres, and the list of games that could qualify is at once vast and mercurial. For my purposes here, though, I’ll be sticking with the following:

A RTS (Real-Time Strategy) is any game which requires the use of strategy and tactics in order to achieve victory in a real-time environment. These games tend to be built around grand strategic simulations, juggling of multiple resources, and complex systems – though not exclusively so. A great deal of focus is put on micromanagement, requiring players to keep track of multiple moving pieces at any given moment.

– Me (2018 college report, abridged). Like I said: I’ve been thinking about this stuff forever.

This is a pretty broad definition, and with good reason: there’s a lot of strategy games out there, and a wide variety of concepts and mechanics for them. Historically, however… if you saw someone using the term “RTS”, there’s a good chance they meant something that looked like this:

These are the classics: the big war-and-society simulators that helped to originally define real-time strategy. They make up what is arguably the genre’s oldest lineage – a mechanical line of descent tracing back to Westwood Studio’s Dune II (1992) – and all share a pattern at the core of their gameplay:

- Build up units.

- Gather resources.

- Brawl for control.

- Repeat, until one side is victorious.

Build. Gather. Brawl. Repeat.

“There was something inherently compelling in Dune II’s core gameplay loop of sending a harvester out to get spice that converted into credits to spend on upgrades, repairs, new units, and new buildings. More and stronger stuff meant less micromanaging the pushback against hassling enemy units. It meant more time to explore the map, set up additional bases, and devise a strategy to thwart your foes. As you played you knew that with every minute that passed your computer-controlled opponent(s) was/were also accruing more resources to build a better base and a stronger army—ensuring that you’d be in for a wearying, drawn-out battle to conquer the map…“

“Westwood had taken the feedback loops of what would soon be known as 4X (eXplore, eXpand, eXploit, eXterminate) games (…) and stumbled on the winning formula for distilling them down into something that could take place on the micro rather than macro strategy scale. Every level was essentially a small-scale, real-time 4X skirmish.”

Build, gather, brawl, repeat, by Richard Moss, 2017

The classic style of RTS has (largely) declined in popularity since the genre’s heyday in the 90’s-00’s – but the genre is absolutely still alive & kicking! It’s just not at a more-than-10-releases per-year level of kicking, y’know? The games are still out there, somewhere.

Which, incidentally, is how we get to the start of this story.

Part 2: Today’s Special

Pocketwatch Games’ Tooth and Tail (2017) is a real-time strategy game set in a faux Russian Revolution, with several factions of woodland creatures embroiled in a war over the world’s food supply. Its gameplay is structured similarly to the classics – with the main loop of capturing resources, building up troops, and repeating – until only one army remains.

The big mechanical twist of the game is that players are locked to control of a single “commander” unit, rather than controlling their troops directly. These commanders have no offensive skills of their own, and defenses that are middling at best. However, all player actions (building construction, soldier movement, etc.) are tied to the commander’s position – literally performed at the point their feet touch the ground.

And that’s… weird. Don’t get me wrong: it’s cool! But also… weird. Which is probably why the idea has been stuck in my brain for so many years.

Or at least, you gotta walk within 20 feet of it before making someone else do it.

Now, the whole “commander unit” concept is not exactly new, nor is it unique to Tooth and Tail. It’s kind of been Pikmin‘s whole deal since 2001. However, in most of the other cases that I’ve personally seen – Pikmin included – the commanders tend to be more of a cross-genre element.

Pikmin‘s captains are puzzle game characters, and they have agency accordingly. They can throw pikmin around, fight enemies on their own, and take whatever actions they need to interact with game’s non-strategic challenges.

Tooth and Tail‘s commanders are, by comparison… nothing. They have no actions besides ordering around units, and even then they don’t have much of a way to do that.

They have one button for summoning a type of units to them, and one for summoning all of their troops at once. Left and right bumper, that’s basically it – the rest is up to your units’ AI.

Tooth and Tail‘s commanders aren’t really a player character – they’re a mouse cursor. They exist purely as a way of selecting points on the map, and limiting how much players can interact with at once. They might be the most tricked-out mouse cursor that you’ve ever seen – but they’re a cursor nonetheless.

What effects does that have on a real-time strategy game? Many.

Part 3: Pro-Cursor Propaganda

Traditional real-time strategy games are – on a fundamental level – games of positioning. You have to think about the structures available to you, and where you can build them. You have to think about where your units are coming from, where you can safely keep them, and how and where they can move. You have to figure out how to get them where you need them in order to win, and how to get them out when things go wrong. Unit movements are perhaps the main vector by which the player enacts their strategy, and the ability to manage them is one of the most important tools in the player’s skillset.

The choice to tie players to a commander immediately upends this, and – in some respects – makes for a system that’s considerably less precise than many of it’s inspirations. The lack of direct control means that you’re never truly able to micromanage your troops, and instead have to settle for something less… structured. It’s less “I’m going to form a carefully-positioned defensive line” and more “I’m going to leave a clump of lizards here, and hope that they beat the hell out of anything that walks by”.

Where Tooth and Tail makes up for this, I feel, is in the player’s movement. You can’t freely order your troops around whenever you need something done, after all. You have to actually go there – and that creates an interesting little wrinkle in the usual RTS tactics. You need to figure out where you need to go, and how you’re going to get there – while continuing to do the same for ~20 of your closest friends cannon fodder.

…And you have to do all of that without dying. Naturally.

Because… yeah. Despite your status as a stand-in cursor, you can absolutely still die – meaning there’s an inherent risk/reward to everything you do. You can’t mindlessly throw units at an enemy turret when you have to walk up to it to target it. You really, really have to play around the openings available to you, taking opportunities to get in close and get out wherever you can.

That opens up the door to sub-game of cat-and-mouse (pun extremely intended), where you can plan around your opponents rather than their armies. Sure, you could structure defenses around the enemy units – but you know for a fact that, at some point, both you and your opponents are going to be running around the battlefield. Why not take advantage of that? It’s easier to shoot one person than 20, after all.

Spot the enemy commander sprinting between bases? They can’t do that if their path is coated in landmines, can they?

This all adds a personal element to PVP – especially in local play – that I find extremely engaging. I’ve spent a lot of time with strategy games like Stellaris where multiplayer is a lot of fun, but tends to be a drawn-out, abstract experience. There’s something about seeing your friend for a fraction of a second – stepping out of your periphery and into the darkness (right as your farm explodes) – that makes for an absolute nail-biter.

It’s a really fun time – even if I always lose.

The result of all of this is something that just feels… different. With all of the running base-to-base, scouting out into the fog, and sprinting right up to your targets you’re doing, Tooth and Tail feels at once more frantic and more personal than most of it’s RTS siblings. It doesn’t feel like you’re playing the omnipotent general in the sky, orchestrating the flow of battle according to your designs. It’s a game about being the lone messenger, sprinting through guerilla battlefields in the knowledge that – should you fail to reach your destination – the fight is essentially lost. And that’s really cool.

…

It’s still not what really gets me about it, though.

Part 4: The Crab Portion of the Essay

So there’s this concept in biology called carcinization. Maybe you’ve heard of it?

This is one of internet’s favorite examples of convergent evolution – the phenomenon where everything keeps evolving into crabs. Or at least, crustaceans do, anyway. They’ve done it at least five times already.

The theory goes that the crab shape is – for a variety of reasons – pretty good at dealing with many of the evolutionary pressures that a crustacean has to deal with. You can scuttle around pretty quickly, you don’t have to worry about getting your tail grabbed by a predator, etc. So, over the course of time, various relatives of shrimp and lobsters have tended towards… crab. They’re not descended from the same ancestors as true crabs, but they sure as hell look like them.

…

Anyways, I’d like to introduce you to Herzog Zwei.

Originally released in the December of 1989, Herzog is the de-facto grandfather of the real-time strategy genre – and one of Westwood’s direct inspirations for Dune II. From the resource-gathering, to the base-building, to the unit management – all the hallmarks of the genre were already there, early on.

The big mechanical difference between Herzog and its descendants was that players were locked to control of a single “mech” unit, rather than controlling their troops directly. These mechs had few offensive skills of their own, and defenses that were middling at best. However, all player actions were tied to… the… mech’s position? Hmm.

…

Isn’t that the same concept as Tooth and Tail?

Part 5: The Consolization of a Genre

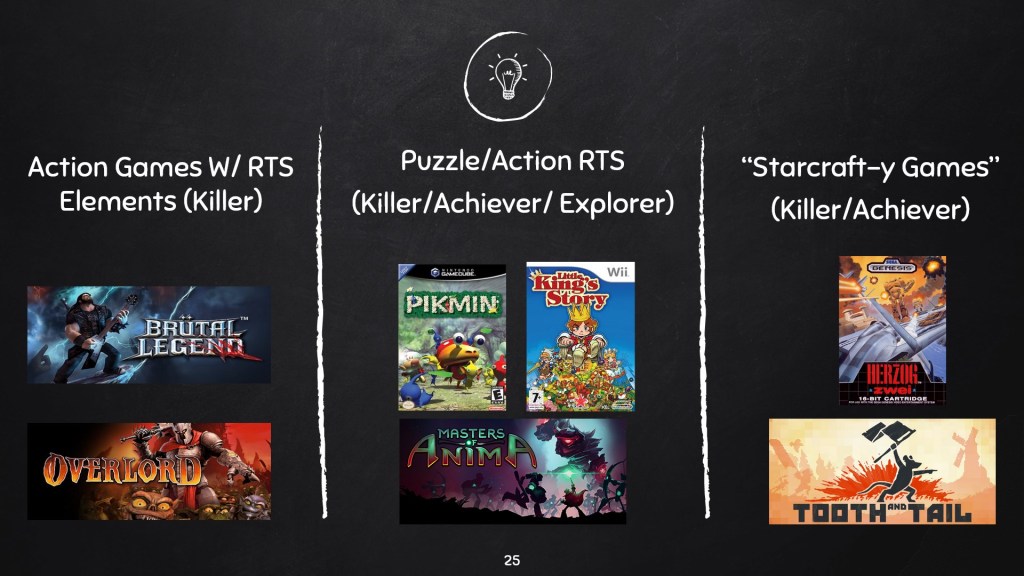

I found this caption and image on a gamasutra article in 2018, and dug up it’s remains for this blog.

Back in August of 2014, Pocketwatch Games’ Andy Schatz did an interview with Kris Graft for Game Developer (née Gamasutra), in which he discussed the early development of LEADtoFIRE – the game that would go on to become Tooth and Tail. The main focus of the article was the game’s controls – and the many challenges involved in designing them for consoles. Or, more specifically:

“How the hell do you fit RTS controls onto a gamepad???”

– Not a real quote, I made this up

And… that’s a really good question! For most of the genre’s history, these games have seen success on mouse-and-keyboard platforms, if for no other reason than… using a controller on them just kind of sucks. When you’re constantly interacting with things all over the screen, navigation via thumbstick is an accuracy nightmare, especially when compared to a mouse’s simple point-and-click. Controller-based RTS games frequently end up having to employ some sort of workaround for being controller-based, like a cursor moved via the thumbstick, or – in Tooth and Tail‘s case – a surrogate player character.

This was also Herzog Zwei‘s solution – which is part of what really interests me about all of this. The history of commander unit mechanics is like it’s own little case study in how game designers go about problem-solving – and the ways they can affect the landscape of a genre.

Game mechanics are often born out of some need in design, whether that be a hardware limitation, part of a gameplay vision, or a concession for the player’s experience. Herzog‘s mechs are no exception – a quirky little control scheme for a strategy game that still has one foot still firmly in the world of Technosoft’s many arcade shooters. It’s a strange choice, and not necessarily more intuitive to use than the control schemes of later strategy games. But, that strangeness makes it feel unique, even amongst its immediate descendants.

The thing is, though, this “unique” mechanic wasn’t really the part of Herzog Zwei that spawned a genre. If anything, it was one of the first things that that budding genre left behind! I mean, sure – Tooth and Tail has it, but for the rest of the genre? It’s true! The entire concept of the mech is extremely specific to the fantasy of Herzog Zwei – and doesn’t really fit a game that’s looking to be a more general war simulation. It was already out of the way by Dune II!

And yet, the concept of the commander unit never really goes away. It continues to pop up repeatedly throughout the history of the RTS genre. And, indeed: sometimes, it’s an explicit throwback to Herzog (Hello, AirMech).

But, more often than not? No. I’m not going to claim to be able to read anyone’s minds here, but I am gonna go out on a limb and say that the creators of Pikmin probably weren’t aiming for the Herzog experience when they chose to center their game around captains. It was just what worked for the game that Pikmin was supposed to be.

Tooth and Tail is closer to Herzog than any other game I’ve played, but we know for a fact that it wasn’t aiming to be Herzog. We know why the commanders are here: the controls! It’s so players can play a strategy game on their Xbox controller and (hopefully) not rip out their hair in frustration!

That formula – the single commanding unit – just happens to be something that works very well on a controller. Those things are practically made to for character action – so real time strategy games tend to oblige them, becoming more character action-y themselves.

It’s just a good idea – so much so that developers keep finding their way back to it.

Sometimes, the creation of a genre is a deliberate process – designers following in the footsteps of a game that came before, modifying and expanding its ideas from generation to generation. Other times, it’s the crab pipeline. Different people, at different places and times, all have the same problems to solve, and the same tools to solve them – resulting in similar patterns. Over, and over, and over again.

And the stories of how they came to be? Always fascinating.

Thanks for reading, and have a great day!

P.S. (Just because I need to pass this otherwise-useless knowledge on to someone):

WAR OF NERVES did this, too! IN 1979! A whole decade before Herzog was even thought up!

There’s actually a long list of games that have done this type of mechanic. Enough that it’s probably not worth me getting into here. Suffice to say, the discussion starts to get pretty hairy at a certain point.

“Like, sure Brütal Legend (2009) starring Jack Black is an action-adventure game, but it’s also got a major RTS element, so you could argue a lot of the core gameplay elements are shared w-“

Nope. I’m 99% of the way through this, and I’m not about to open that can of worms. I think I’ve made my point enough.

Oh, and one final thing i couldn’t quite work into the essay proper…

PSA for the fellow Pikmin enjoyers out there: Oddsparks just went into early access recently. If you even remotely like Pikmin, you should try it. It’s one of those “oops, I just spent 6 hours on the demo” games.

One response to “My Life as an Upjumped Cursor”

[…] frequent updates on my progress again. Then, I immediately fell down a rabbit hole writing about strategy game design. […]

LikeLike