QA-Inspired thoughts on dice, RPGs, and the ways that stats work.

Hello. Welcome to the blog.

This is my second piece about The Dragon’s Table TTRPG – the tabletop game I’m currently QA testing. Where the first post I wrote was kind of a spur-of-the-moment thing – something to break up the hours of debugging – this one has been kicking around in my head for a few weeks now, and I need to put it to words before it eats me alive. Metaphorically.

As a result, this one’s going to be a bit different; unlike most of my writing here (where I ramble about whatever I’ve done in the last week until some semblance of a point emerges) – I’m going into this one with a specific question in mind:

In TTRPGs, why do we always try to roll high?

Part 1: The Reason I Can’t Stop Thinking About This.

A Problematic Mechanic

As with most things good things in my life, the idea for this popped into my head unceremoniously at about 2 a.m. on a Thursday night.

This particular Thursday happened to fall a couple hours after a session of The Dragon’s Wasteland – a weekly campaign where we (the game’s testers) try out changes and give feedback. Our DM, Samantha, is also the creator of The Dragon’s Table, and tends to take what she learns from our sessions to the drawing board every few weeks.

She also likes to use us as the guinea pigs for her new ideas – which is, of course what we signed up for as testers.

However, I do feel obligated to point out that TDT is a dark fantasy system, meaning there’s a large part of the game dedicated to enabling players to, make very, very bad decisions – and then ensure that they face even worse consequences. Which means that we get to test many fun scenarios, such as:

“How many party members can get their skin ripped off before this monster dies? :P”

(The answer was two, by the way.)

However, this particular week, one of the new things for testing was the overkill mechanic – a mechanic which proved to be… interesting. Controversial, even.

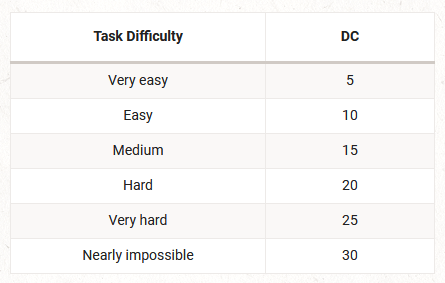

The overkill rule allowed a DM to set an upper bound on the game’s dice-roll-based skill checks – where high numbers could roll over into negative effects. The example scenario provided that night was a magical barrier, with a small opening that could be widened for players to pass through. The breakdown of the how rolls could play out looked something like this:

Player Rolls Below

Requirement

< 10

Fail to widen the opening.

Player Rolls Above

Requirement

>= 10

Widen the entrance.

Player Rolls Above

Overkill Threshold

> 32

Widen the entrance – but it sustains some damage.

Don’t think too hard about these numbers. I just made them up. I don’t know the originals 🙂

Now, to someone looking in from the outside, I imagine that this design choice might seem a bit arbitrary. Perhaps even a, “wait, but why?” sort of thing. And to some degree… yeah! You’d be right.

In the design language and conventions of D&D-adjacent RPGs – higher stat values aren’t a measure of raw power, so much as an abstraction of skill. Your strength stat in 5e is not always how strong you are, but how good you are at things related to strength – feats of athletics, aiming weapons, etc.

Putting an upper threshold on dice-rolls, then, becomes… weird. It creates situations where your masterful wizard can be… too proficient in magic for a weak target? Where a warrior who has dedicated their life to martial arts can’t control the damage they inflict? It produces the sort of results that make you go:

“Yeah. I get it. A 37 strength roll is overkill for twisting a doorknob… but still!”

For this reason (and the fact that we’ve got characters whose stats are already a bit up there), this wasn’t a particularly popular mechanic among testers that night. Myself included.

However, all of that said, I’d argue that there’s actually some sound design logic at play here for why you’d want a system like this – especially in The Dragon’s Table.

Let Me Explain.

Mechanically, thematically, and aesthetically, The Dragon’s Table reads like a designer’s love letter to the Faustian Bargain – a set of systems dedicated to representing power, and the consequences of obtaining it. It provides a setting where reaching near-godhood is an alarmingly achievable feat, and where several several generations of ruling societies have done just that – to fairly tragic results.

The mechanics surrounding characters are reflective of that – with a host of different ways of pushing both abilities and stats beyond mortal limits. Many of these already come with in-built consequences, some more… involved than others.

I feel like Sam wouldn’t like me spoiling any of the fun, secret details here – so I’ll let her explain her design goals for herself :p

“…I want the characters to end in a worse place than they started. The world that I’ve built is designed to chew up units and spit them out irreversibly changed, and I’m trying to make sure that if something seems too good to be true, it always is.”

I also don’t want danger to be a surprise. I think lots of “hard” games get their reputation from the fact that they’re super easy to die in, and losing a character is no fun at all. I wanted to create a system where dying is incredibly rare, but the long drawn out process of “the downward spiral” is fun to enjoy for players and GMs :)!

Also, I wanted a system that serves as a direct answer to min-maxers and problem players. If you try to take advantage of the world, the world will kill you, and you’ll get to look at the exact place in the manual where it says how :).”

– Samantha Arehart, to me, 12/17/2023

Thanks, Sam 🙂

However, as we’ve been testing late game content – and the upper limits of what’s possible – there are some methods of empowering characters that are clearly a bit too consequence-free. Things along the min-maxing axis of gameplay.

Naturally, you could just make those things less effective. But, honestly? Pushing a character’s power level like that is very much in the spirit of the game – so it’s worth giving alternative solutions a try.

The overkill thing was, in my understanding, less about punishing players, so much as defining an upper bound on possibility. It’s establishing a threshold that represents the absolute maximum of what a mortal character can do, then turning to your players, and saying:

“You can go beyond these limits – but you won’t be in the realm of a normal person anymore if you do it.”

This was, of course, a test mechanic – and a day-one test mechanic at that! The implementation of it still felt kind of arbitrary, since players can’t really control how low they roll their dice. As Sam herself put it:

“I wanted there to be some checks that required a precise touch. The idea is that these specific checks would be heavily telegraphed, but it’s a needlessly overcomplicated system and I’d rather put my energy into different things.”

– Samantha, again. 12/17/2023

We’ve since tested some alternatives that play a lot more smoothly, in my opinion. So, all’s well that ends well!

…

And then, the thought that’s been tumbling around in my head like a D20 since 2am that Thursday:

Huh.

“…players can’t really control how low they roll their dice.”

Wait… why can’t we do that?

Part 2: Number Go Up?

At this point, I’m going to put a brief disclaimer that the ideas here are based on my observations about the things that I’ve seen, played, and read. I’m going to be saying some things about the nature of dice rolls in tabletop games, and if you have a counter-example to my point, then… yeah. You’re probably right. I fully expect that they’re out there somewhere, and I just haven’t seen them. I’m not that smart.

That said – have you ever tried to flub a roll in Dungeons & Dragons?

Don’t get me wrong; there’s plenty of ways you can absolutely, hilariously throw in TTRPGs. It comes with the “RP” part of the genre. But, in D&D, Pathfinder, whatever – have you ever just… tried to roll a five on something you’re good at? For entertainment, or otherwise? You can’t do it. Not without some careful manipulation of debuffs or disadvantage.

Meanwhile – do you need to roll higher? Need to clear a DC 20 after rolling a 10?

Done. Easy. There’s plenty of ways. Modifiers, stats, skills, buffs, advantage, and so on. As many ways as there are stars in the sky. Even down to the structure of level-up and stat systems, the arc of TTRPG design stretches eternally into the horizon of big number.

“The way you do that in Dungeons & Dragons, though, also assumes higher-than-average capacities: You roll four six-sided dice, drop the lowest score and add up the others. Alas, “The Veech” turned out to have ridiculously high stats in every category. He was as wise as the oldest monk, as formidable as a brick wall. He was persuasive as a seasoned used car salesman and as strong as, well, a guy who was pretty strong. His lowest stat was intelligence, which was just one point below average. “The Veech” was too capable, and we hadn’t even started the game yet.”

It Is Surprisingly Hard To Create An Incompetent Ass-Clown In Dungeons & Dragons

(Cecilia D’Anastasio, Kotaku, August 8, 2019)

This is (obviously) not true across the entire spectrum of games; there are many different ways of measuring and quantifying success player success, many of which aren’t even numeric. But, in the context of TTRPGs, it certainly does seem to be that bigger is (generally) better.

Why do we do it like that?

Now, that’s not really a design problem, per se. In fact, there’s plenty of good reasons why we do that.

For one thing, in terms of communication, it’s pretty easy to understand the idea that the bigger number wins. Regardless of what game, math is a consistently a big generator of friction in the tabletop experience, as anyone who’s ever spent minutes checking (and double checking) every number on their character sheet knows well. Worrying about rolling too high would only add more to that.

In general, this way of approaching numbers also dovetails nicely with progression. The 1-to-1 correlation between your stats going up and your character getting better is a simple, clear reward for playing, and the idea that your stats could get too high immediately complicates that. As we saw with our overkill test in The Dragon’s Table, the mere suggestion that your character build could undergo a bell curve – becoming worse again at a certain point – is just uncomfortable, even if the threshold for that is so high that you’d never reach it under normal circumstances.

In summary, “big number, better number” just works! It’s a good way of doing things!

However, it’s clearly not the only way of doing games, as the mere existence of golf proves. It’s a matter of circumstances, flavor, and what qualities you want your mechanics to evoke in play.

So, what are those circumstances?

Part 3: Small Numbers and Weird Saves

Earlier, in the section about testing The Dragon’s Table, I talked a bit about the “why” behind messing with dice-roll mechanics (defining mortal limits). While I didn’t feel that TDT’s systems quite supported what overkill was trying to do, the idea behind it was – for lack of a better term – “neat”, and is one of several reasons I can think of where someone would want to turn TTRPG number conventions upside down.

Player Expression (and the Minigame of Managing Your Damage)

In a more recent test session of TDT, we had an encounter with a particular bastard of a bandit. He was a real P.I.T.A – but one of those villains whose presence was entertaining enough that we were a little divided on fully killing him.

There was an attempt by some (me), during combat, to keep him alive, maybe to give him a chance to be a better person. It didn’t work out that way, unfortunately, on account of all the extensive blood loss. Whoops.

There’s already punch-pulling and sparing mechanics in many TTRPGs, of course – but there’s something fun about trying to manage and limit your damage output. It’s the same principle behind capturing a Pokemon in battle – an alternate objective within a combat system normally focused on getting enemies to zero.

“In Which Brennan Lee Mulligan Rips Someone’s Arm Off”

As stated, higher tends to be better in TTRPGs – so abruptly reversing that is a great way to cause immediate panic in your players.

This section contains a video with spoilers for Critical Role’s Exandria Unlimited: Calamity, Episode 4. If you care a lot about that, you can skip the video and just read the text!

As this clip from EXU demonstrates, suddenly – but clearly – switching up the usual conventions is an excellent shorthand for something about their current situation being very, very wrong – and implies that the consequences of doing the thing that they’re trying to just might be worse than the cost of failure.

An “Are you sure you want to do this?” if you will.

MONOPOLY.

I promise this one is related to TTRPGs. Please bear with me.

Monopoly has a bit of a reputation in game design – and among players, for that matter. As a derivative of The Landlord’s Game – a demonstration of the random, unfairness inherent to a system of landlords and property ownership – it’s use of dice-based movement is (unsurprisingly) random. You have little control over where you’re going, and can only really go forward in circles until the game is won.

I end up playing Monopoly once or twice a year with my parents (it’s their sort of board game), which is how I had the opportunity to try Monopoly Gamer: Mario Kart.

This is what it says on the tin: Mario Kart-themed Monopoly, with the fake dollars switched out for coins, roads for races, etc. However, it also does something interesting: allowing players to spend the coins they accumulate to add additional distance to their movement rolls.

This small change has a drastic effect on the way that movement behaves. While you still can’t subtract from a dice roll, you can control where you end up, to a degree – which is a big deal for a game where the specific spaces you land on determine whether you win or lose.

Putting aside any implications this has for the original message of Landlord’s Game, this is (in my opinion) a marked improvement to Monopoly‘s movement system, and weirdly demonstrates the value of using targets alongside random rolls. It creates a pattern of holding and expending resources not too dissimilar to the way players use buffs and bonus actions in D&D. It just shifts the decision-making – from how much you want a roll to succeed, to what outcome you want from from it.

Part 4: Quote-Unquote Conclusions

The fact that this TTRPG post has a section dedicated to Monopoly feels absurd, even as I’m writing it – but I’m convinced that there’s something of merit here. What form that takes, I’m not certain, but the idea of doing something weird with it has absolutely taken hold in my brain.

Maybe a system where enemies have target numbers where they’re vulnerable? And identifying what those are is part of the system of combat? Something similar for lock-picking, and other skill checks?

Maybe a variation on the typical modifier system, where your stat modifier is a value you can add/subtract up to from any roll, instead of a fixed add-on?

I don’t know! None of these are fully-formed concepts, nor is anything I’ve said here a formal critique of the way RPGs work now. If anything, this is the WordPress blog equivalent of waving my arm at the game designers of the internet, and screaming-

“There’s an idea here, right? I’m not losing it, right???“

-while juggling development on two games and an I.T. job. I’m busy!

…

Anyways-

The Actual Conclusion Within the Conclusion

I took my sweet time in writing this. Within that time, Sam has made several more updates to The Dragon’s Table – including to the mechanic that started all of this.

Overkill is over.

In spite of everything that I’ve said was neat about it, it still didn’t quite work with the game’s mechanics, as they are. We talked a bit about the design behind it, and decided that it’d probably be better to keep the scope of the consequences narrower, and more tied to the methods of acquiring higher stats.

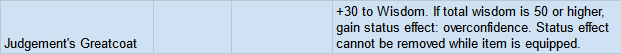

For example, Judgement’s Greatcoat – notoriously powerful stat-boosting item – now institutes it’s own bell curve effect, where your character’s overconfidence causes all critical successes to count as critical failures instead.

This is far more reasonable to deal with, as both a player and game balancer.

It also has the side effect of being extremely funny when, for example, you start rolling non-stop natural 20’s the session the effect is introduced.

(That last anecdote is about me. I did that.)

But, that’s why we test these things, isn’t it?

Fin.

At the end of the day, I guess the “thesis” of this post is that we use high numbers as an indicator of success in TTRPGs because it makes sense – but doing it other ways can be pretty entertaining, too.

Did I need to spend this long writing to make that point? Maybe not. But now all those dice thoughts are out of my head, at least.

As always, thanks to Sam for letting me test and write about her game, and for contributing her own piece. You should go check her out! She does art good, too!

Sam Arehart (DT75ART)

She/Her, Game Artist, samanthajarehart@gmail.com for freelance inquiries. Go follow @DragonsTableRPG on Twitter!

Click the image or this for more links!

After writing most of this, I asked her if there was anything she wanted to add, and she said it might help if-

“…your readers knew I’m an evil person who loves games with jank design.”

-and that she’s-

“…emulating the vibes projected by a 3-way Venn diagram between Drakengard 1, Pathologic Classic HD and FE5.”

So… interpret that as you will 🙂

As for me… I don’t know what my timeline for anything looks like right now, honestly, given the looming holidays. But regardless, thanks for reading this!

Have a good one!

Leave a comment